A shadow board is one of the most common options for tool storage found in amateur and professional workshops and sheds the world over. Its noble aim is to organize the workplace so that tools are near the work station where they are to be used.

|

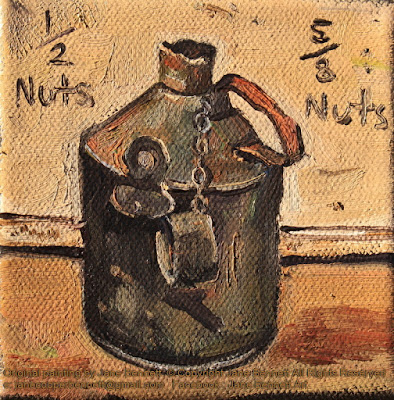

Work in progress on the easel

E135A 'Shadowboard - No Brake' 2017

oil on metal panel 51 x 51cm

Available |

Shadow boards have the outlines of a work station's tools marked on them, so operators can quickly identify which tools are in use or missing.

As well as providing easy access

to tools,they are supposed to reduce time spent searching for the correct tool; to reduce losses due to carelessness, lack of proper maintenance or theft; to improve work station safety as tools are replaced safely after use, rather than becoming potential hazards; to reduce clutter; and to maximize the space available.

|

Work in progress on the easel

E135A 'Shadowboard - No Brake' 2017

oil on metal panel 51 x 51cm

Available |

Well that was the Platonic ideal anyway.

The dream of imposing order on chaos is often cruelly exposed as exactly that - a dream, when reality kicks in.

How should a shadowboard be organized?

Sounds so easy and straightforward, but it reveals fundamental and often irreconcilable differences in temperament, age and level of expertise, and can be the source of perpetual bickering, even long-running feuds.

|

Work in progress on the easel

E135A 'Shadowboard - No Brake' 2017

oil on metal panel 51 x 51cm

Available

|

Should it be organized by type of tool (all spanners, screwdrivers etc grouped together), by size (aesthetically pleasing to have a hierarchy of tools descending by size, but not necessarily the most practical), by frequency of use (commonly used tools in the middle where they are easily removed or replaced) by ease of removal /replacement (large, awkwardly sized or heavy tools placed where people don't have to reach up or down for them) or by what is required for common tasks (a particular size of wrench/saw/hammer/screwdriver etc are often needed together for a task that crops up frequently).

Sometimes it can even be a passive-aggressive wish list, like a recent commercial for a hardware line of products where empty outlines were left for needed or desired tools, either in hope of a future financial windfall or thoughtful gift.

|

E135B'Shadowboard with 44 class diesel

-(Do not pull all way out) '

2017 oil on metal panel 51 x 51cm

Available |

The usual result is a hotch potch of all the above.

Jumble of the useful, the once useful and now obsolete, the broken bits, the spare parts that 'may come in handy'; the lost, strayed and some frankly useless items that seem to breed unchecked in dark corners. When, if ever, were any of these used? Last week? Last century?

|

Work in progress on the easel

E135B'Shadowboard with 44 class diesel

-(Do not pull all way out) '

2017 oil on metal panel 51 x 51cm

Available |

I used metal panels to paint on instead of my usual canvas, leaving the metal bare when the tool was shiny and well maintained, and only painting the non-metallic or rusty parts. The work above also includes a 44 class diesel lurking in the background.

The faded, naive lettering found on cryptic signs create abstract yet evocative grids of letters and word fragments, colour and text fading into meditative, elegiac compositions.

Other mysteries abound. As this is a workshop filled with tools and presumably people who know how to use them, why did someone bother to write "Do not pull all way out" on the drawers of the cabinet beneath, instead of fixing the drawer?

I'm no handyperson, but even I can fix drawers - it's fiddly but not that hard.

|

E135A 'Shadowboard - No Brake' 2017

oil on metal panel 51 x 51cm

Available

|

A massive Marie Kondo attack has been carried out in the Large Erecting Shop to tackle decades of clutter. Nothing to do with sparking joy.

Everything deemed not strictly necessary to the re-purposing of the Large Erecting Shop as a running shed is being given the old heave-ho - best case scenario sent to Thirlmere, worst case - the skip.

I

was chased from one end of the shed to the other, as wherever I set up

my easel, I seemed to get in the way. I was hunting for a quiet corner

as the situation brought out crankiness in normally laid back people. I

was incessantly asked "why I was painting this rubbish instead of the

trains", but most of the trains will still exist somewhere, while this

sort of subject, evoking the true spirit of the workshop, is ephemeral.

But fashions change as to what is deemed 'necessary' and unique and quirky items can be lost or destroyed in the rush to impose order on chaos..

In the Large Erecting Shop the shadowboards are no longer functional as no repair or maintenance will be carried out there.

Ghost boards with ghost signs for ghost trains.

They show the never to be filled outlines of lost tools for lost purposes.

Headstones of the workshop.