Cockatoo Island, the largest island in Sydney Harbour, is located at the intersection of the Parramatta and Lane Cove rivers. It is the last vestige of the era of the Industrial Revolution remaining in Sydney.

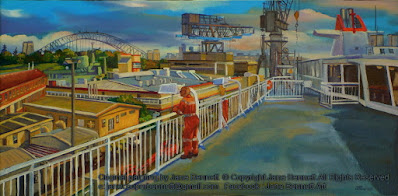

CK8B & CK52 Crane & slipway from the Officers headquarters

1989 & 2007 oil on canvas 61 x 46cm

CK8B & CK52 Crane & slipway from the Officers headquarters

1989 & 2007 oil on canvas 61 x 46cm

Between 1839 -1869 Cockatoo Island was a prison colony.

The inmates not only excavated the 2 tunnels and 2 graving docks that nearly bisect the island, but to add insult to injury they even had to build their own gaol using the excavated sandstone of the island! The only successful escapee was bushranger Captain Thunderbolt (his more prosaic real name was Fred Ward), who escaped on 19th September 1863.

After its stint as Sydney's 'Alcatraz' the island was used as a graving dock, reformatory and industrial schools, and a major shipbuilding site.

In the early twentieth century Cockatoo Island became one of Australia’s most important industrial sites where ships were built, repaired and modified. Thousands were trained and employed there. I still meet people who did their apprenticeship as a boilermaker or fitter and turner on Cockatoo Island.

As the progressive removal of tariffs, regressive government policies, the high dollar and the pressures of globalization helped kill off Australian manufacturing, the focus of employment has turned increasingly to tourism, entertainment and service industries.

Most of Sydney’s former sites of industrial and maritime activity have now been gobbled up by developers for monolithic dormitories of beige apartment blocks. After many political battles, some remaining industrial structures of Cockatoo Island have been retained, against all odds. Although some large workshops, slipways, wharves, residences and other buildings remain, such as the Turbine Shop and the Mould Loft, many major buildings were demolished after Cockatoo Island closed as a dockyard in 1991.

Now it's a UNESCO world heritage site and its industrial ambience has been exploited for many cultural events. It was the site for the filming of X Men Origins -Wolverine and several 'reality' programs. Since 2008 it has been the flagship venue of Sydney’s Biennale. However, its original function as part of Sydney’s rapidly disappearing Working Harbour, has gone forever.

When I was 'Artist in Residence' there in the mid-late 1980s and then again in the early 2000s, I was the only artist on the island.

When I was 'Artist in Residence' there in the mid-late 1980s and then again in the early 2000s, I was the only artist on the island.

For the last decade,

the public has been allowed to visit the island, but when I painted the

2nd canvas in 2007, it was still off limits. The Sydney Harbour

Federation Trust was frantically fixing up the infrastructure to be able

to open it to tourists. I would travel by barge at the crack of dawn

from Mort's Dock with the other workmen.

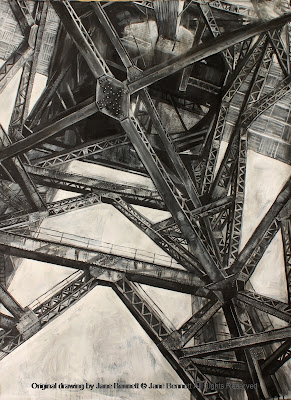

CK8B 2 Cranes on the North-West Slipway

1989 oil on canvas 61 x 46cm

Enquiries

CK8B 2 Cranes on the North-West Slipway

1989 oil on canvas 61 x 46cm

Enquiries

I started painting on Cockatoo Island in the mid 1980s when it was still operational and submarines were still being refitted there.

I'd have to sign the Official Secrets Act and promise faithfully not to paint any submarines or sell any of my paintings to the Russians. I'd leave my easel, paints and table in the office of the Ship Painters and Dockers building between Fitzroy and Sutherland docks.

There was a sign "Pro Painter Foreman" on the door, which always made me laugh. I was so naive that I didn't know anything about the reputation of this notorious union!

These two canvases were painted at the same location,the north - western slipway, at the same time of day, at the same time of year and on the same format canvas - but 18 years apart.

CK52 Crane & slipway from the Officers headquarters

2007 oil on canvas 61 x 46cm

Enquiries

The most obvious difference between the 1989 and 2007 paintings is the omission of the pale green crane, a casualty of a storm not long after the 1989 canvas was painted.

This was the Butters crane, purchased from the Whyalla Shipyards in 1979, when Cockatoo Island was trying to adopt more innovative strategies,for the construction of HMAS Success in 1983-4. The rather forlorn looking crane left on its own in the 2007 painting, was the ex- West Wall crane, also a comparatively recent addition to the island, as it was relocated from Garden Island in the 1970s.

This partial modernization was a false dawn, however, as HMAS Success would be last ever ship built and launched at Cockatoo Island. Less than 8 years later, the island was closed.

Related Posts

Article written by Steve Meacham in the Sydney Morning Herald

.jpg)

.jpg)