"It is with fire that blacksmiths iron subdue

Unto fair form, the image of their thought :

Nor without fire hath any artist wrought

Gold to its utmost purity of hue.

Nay, nor the unmatched phoenix lives anew,

Unless she burn."

Michelangelo, Sonnet 59

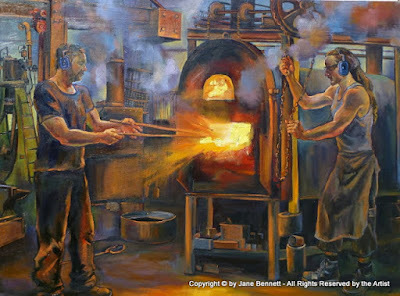

I've finally completed my portrait of Chris forging chisels.

.JPG) |

Portrait of "Chris Sulis forging chisels"

2011-12 oil on canvas 152 x 122cm .

|

.JPG)

|

Portrait of "Chris Sulis forging chisels"

2011-12 oil on canvas 152 x 122cm.

|

In Renaissance and Baroque paintings, the artist would often paint dark red velvet drapery fluttering behind the subject. The dye used for this colour was extracted from the murex shell.

It was prohibitively expensive and difficult to obtain, so using it as a backdrop would emphasise the aura of aristocratic power. Think of the background to Van Dyck's portraits of the pre-Civil War English court or Titian's portraits of the Papacy.

My luxurious crimson curtain is actually the welding screen, but it does give a feeling of the lost glories of the past.

|

Detail from Portrait of "Chris Sulis forging chisels"

2011-12 oil on canvas 152 x 122cm .

|

|

"Time for Safety" detail from Portrait of "Chris Sulis forging chisels"

2011-12 oil on canvas 152 x 122cm

|

A decrepit "Time for Safety" sign is propped against the arched window frame. It reminds me more of a late Victorian moralizing

wall plaque than an early example of Occupational Health and Safety regulations.

|

"Time for Safety" detail from

Portrait of "Chris Sulis forging chisels"

2011-12 oil on canvas 152 x 122cm

|

These days people have become risk averse to a ridiculous degree. In doing so they lose the chance to turn their fear into courage.

To paraphrase an old song, there is a time for safety and there is a time for risk.

Being an artist is risky. Doing anything interesting is always inherently risky.

Risks aren't always obvious.

The major risk to the blacksmiths isn't their hair catching fire, as they are too skilled. The real threat is that a combination of economic and political conditions could make their entire existence no longer viable.

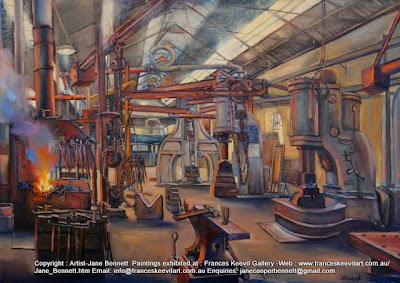

I'm now touching up the background of this painting of a different stage of the chisel forging process. This painting shows Euan crouched in the centre as the Massey hammer pounds the point into shape.

I'm very happy with both of these paintings.

So happy that next week I'll enter the painting of Chris in the Archibald Prize and the one of Euan in the Sulman Prize at the Art Gallery of NSW.

I'm not famous and neither are they, so I haven't a prayer with either

work.

I'll waste $60 and half a day delivering them, but I feel like entering just

for a stir.

Might as well be hung for a sheep as a lamb.

Unlike most of the

entries, these haven't been whipped up just to enter a prize but

are part of my normal work. I'm sick of the typical Archibald formula

for prize winning entries - a giant close up of a head, without context

or content, painted from a slide projector.

|

Detail from portrait of

"Chris Sulis forging chisels"

2011-12 oil on canvas 152 x 122cm

|

I hadn't originally expected this to be a portrait, but one of a series of paintings of the process of chisel forging.

The previous painting showing Euan at the hammer is a very good likeness, but the figure is in the midground, although he is the focus of the whole work. The blacksmiths could not "pose" for me in any formal sense of the word, or even stay still for more than a few seconds as they were very busy working to their deadline. I took an immense risk painting a large full length figure dominating the foreground in a pose that he could not sustain for longer than a few seconds. I had to watch and wait whilst immersing myself in their world. The more I painted Chris, the more his pose seemed to gather authority and purpose.

As I have painted Chris

doing the work that he loves in the place that he loves, this painting

will probably be tagged with the pejorative term "genre piece". Yet it

tells you more about the thoughts and values of the subject than most

Archibald portraits.

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)